- Home

- Allison Norfolk

The Dragon & the Alpine Star

The Dragon & the Alpine Star Read online

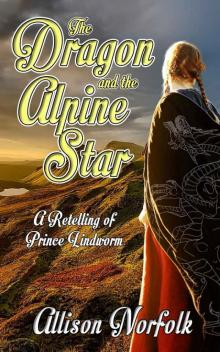

The Dragon and the Alpine Star

A Retelling of Prince Lindworm

Allison Norfolk. The Dragon & the Alpine Star Copyright © 2019 by Allison Norfolk. Cover design by Robert Snare All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any number whatsoever without written permission of the author, except in the case of quotations embodied in articles and reviews. This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination, or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Contents

Title Page

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Epilogue

Author's Note

A Sneak Peak at Poppies & Roses

Prologue

Early September 1883. Schloss Laxenburg, Vienna, Ausria.

The feeling of excitement and dread was almost palpable in the castle as August wore on and on. The Crown Princess of the Austro-Hungarian Empire was due to give birth to her firstborn any day. If it was a boy, the Empire would have an heir, and the Habsburg line would continue on the throne for another generation. If it was a girl, while she could not inherit the Empire, it would at least be proof of the Crown Princess’s ability to have healthy children. She and her husband, Crown Prince Rudolf, could try again soon with reasonable hope of success.

If the Crown Prince’s absence from this momentous occasion was whispered about among the servants, then that was a minor matter. And if the gossip rags placed him drinking and dancing with women of ill repute while his wife marked time until their child came, anyone of consequence closed their eyes and pretended not to know while the staff only spoke of it in the lowest undertones. The birth of the child would overshadow any other discussions in the Austrian Court for weeks.

As for the Crown Princess herself, Stéphanie of Belgium, the gossips could not decide whether she knew or cared where her husband was. Whispers had followed the pregnancy from the beginning, although only among those in proximity to the Prince and Princess. While their marriage had begun happily enough—it had been a love match—warm feelings had quickly cooled on the heels of the Prince’s refusal to give up his other women. It was not general knowledge how little time they actually spent in one another’s company while out of the public eye. Exactly how little was a matter left to speculation, though if pressed their personal body servants would only hint that the royal couple hadn’t spent the night together in quite some time. The Prince’s valet would get a small wrinkle between his brows, and the princess’s maid would press her lips together until they were white at the corners, but loyalty to their employers kept them from doing more than that to express exactly how worried they were.

That the Princess was pregnant, there was no doubt. The best doctors in the Empire had confirmed it, and two of them were in residence at Laxenburg Castle to attend the birth and to send daily updates on her condition to her father-in-law, the Emperor, and mother-in-law, the Empress. The pair had been chosen precisely because they were professional rivals, and therefore what one might omit in his report the other would be sure to include. Therefore the Emperor and Empress, estranged for many years themselves, tended to receive wildly differing reports. The one thing the doctors agreed on was that the Princess was indeed expecting, and that labor could commence at any time.

Had they desired to consult with each other, they might have found themselves in agreement on one other thing: both suspected, in their heart of hearts, that there was a chance the Crown Princess was carrying twins. There was no way to be certain, but if they had been chosen due to their rivalry, they had also been chosen due to their combined years of experience.

The most telling piece of evidence for the theory of two babies was the most simple: how large the Princess had grown. Her ornate gowns designed by the cleverest Viennese and Parisian seamstresses concealed this fact during the Princess’s time outside of her apartments, but those few who saw her in private were always surprised that her child—or children—hadn’t kicked their way out of her. Even standing too long was a strain for her of late.

The child was also unusually active, even for twins. The Princess bore dark circles under her eyes due to lack of sleep that even face powder could not quite conceal. She confided to the doctors that the child seemed awake at all hours of the day or night, such that it was impossible for her to catch more than a few minutes’ rest at a time. At times the kicks were even painful.

The Princess’s maid, listening to her mistress’s conversations with the doctors, pressed her lips tight together and wondered whether that was all the Princess was losing sleep over, or if she worried about something else.

The maid knew, in a way almost no one else save the Princess herself could, that there was something near-miraculous about this pregnancy. The maid had her private, unexpressed doubts about the identity of child’s father, but being so close to the Princess also meant she knew exactly who was in proximity to her mistress any given time. While the father might or might not be Crown Prince Rudolf, the maid knew for certain it couldn’t be anyone else, either. Philanderer the Prince might be, but the Princess was another story altogether. She was a devout woman who took her vows before God very seriously.

And the poor maid didn’t quite dare ask the Princess for details. Something about the quiet, desperate light in the Princess’s eye told her that if she did get an honest answer, it was almost certainly going to be one the maid would not be happy to know. So whatever her suspicions, she kept herself blissfully, purposefully ignorant, and refused outright to join in any other household speculation except to defend her mistress against any hint of spending time with any man other than the Prince.

Whatever else, the integrity of the Hapsburg bloodline must be protected, and with it, the stability of the Empire.

When labor at last began in the early hours of the last day of August, the maid was kept busy fetching and carrying all that the doctors required. The Princess had her ladies-in-waiting, companions of good birth and not a commoner like the maid, who would stay by her and offer comfort.

The doctors argued at first and there was a great deal of fuss and noise every time the maid entered the bedchamber. But as the day slowly slipped into evening, they grew quieter and quieter. The attendants began taking turns sitting with the Princess and resting themselves.

Things continued the same the next day, until finally in the late afternoon the maid came in carrying an ewer of warm water to find the room empty but for the two doctors, deep in consultation with one another. It was the first time the maid had seen them having a remotely civil conversation and she was so surprised she froze. The slosh of water attracted their attention.

One opened his mouth, and the maid sensed she was about to be banished. The other doctor caught his colleague’s sleeve and murmured, “She’s the Princess’s personal maid.”

They looked at one another for a long moment, then nodded once, decisively.

“Come here, girl,” the other doctor said, beckoning. The maid put aside the ewer and approached.

“Yes, sirs?” she said, curtseying.

“Go into the city and find this address,” said the first doctor, pressing a piece of

paper into her hand. The maid looked, and saw that this house was located in a respectable district. Not wealthy or prestigious, but generally populated by prosperous tradespeople, doctors, lawyers, and craftsmen who made fine things for the wealthy. “Ask at the house for Frau Silber. Tell her she is to attend a birth of suspected twins and she will be paid whatever she asks, but do not tell her who you are summoning her for. Wear decent clothes that don’t show any royal livery. Bring her back here once it gets fully dark.”

“Yes, of course.” The maid shot a frantic look at the bed, but she couldn’t see more than a lump under the covers.

“The Princess is getting what rest she can,” said the second doctor. He actually patted the maid’s shoulder. “You can help her best by fetching Frau Silber. Go on, now.”

The maid fled. She did exactly as instructed, finding the house without difficulty.

Frau Silber turned out to be a younger woman than she’d thought, perhaps in her early thirties. Somehow the maid had pictured a midwife—for certainly this must be the woman’s profession—as a grandmotherly woman with white hair. But the woman appeared competent for all her youth. She asked no questions, gathered a basket that seemed to be mostly packets of different herbs (the smell was so powerful the maid sneezed and started breathing through her mouth), and followed the maid into the night. The midwife didn’t seem unduly shocked when she saw they were going through a little-used side gate into the castle grounds. She said nothing, and did not hesitate. The maid led her through a concealed servant’s passage to the royal apartments.

The doctors looked both relieved and wary when maid and midwife entered.

“Well, I won’t waste time with any smugness that you had to call me in, even though I warned you,” the midwife said. “We have patients to save. Come, let’s begin. You may, of course, be assured of my discretion.”

The doctors relaxed as the midwife began to choose bags of herbs and spread them out on a convenient table the Princess normally used for writing daily letters and in her private diary. “Hurry,” said the first doctor. “We don’t have much time before her ladies realize they were all sent away at the same time.”

“This shouldn’t take very long,” said the midwife, her eyes and fingers never wavering from her work. “A little encouragement is all that’s wanted, now that there’s privacy.”

The curious maid hovered in a corner, knowing she probably should leave but feeling a strange compulsion to stay in case the doctors or midwife needed to send for anything—or anyone—else. No one noticed her, and indeed the others in the room appeared to have forgotten her entirely.

Unlike the doctors, the midwife used no implements. She sat on an upholstered stool beside the Princess’s bed, asking questions and receiving answers the maid could not hear. Whatever was said, it seemed to be what the midwife was expecting. She nodded once. Then she stood and went back to her herbs. She mixed some from several packets together until she had two separate handfuls. These she lifted from the table and carried carefully to the bed, fingers clenched around her full palms and hands held out straight in front of her.

All of this the two doctors stood by and watched, their expressions a strange mixture of awe, resignation, hope, and resentment. Their rivalry seemed to be completely set aside, and they might as well have been twins themselves, their faces were so alike in those silent minutes.

The midwife knelt on the bed beside the Princess, who also had been oddly silent when before she had been groaning off and on, and with her hands held carefully over the Princess’s swollen abdomen the midwife mixed her two fistfuls of herbs together and then released them. As the dried plants fell, the maid would almost have sworn they took on an ever so slight glow.

The Princess’s belly heaved. To her credit, the Princess did not scream, though she let out an involuntary strangled-sounding noise as she choked back her reaction to whatever was happening inside of her.

Something—and the maid thought it might be green—scampered through the disarrayed silk bedclothes, across the floor, and up onto the nearest window ledge. The window had been left cracked, as summer’s heat had not let the city go. The maid got a quick glimpse of a long tail, with a pointed tip that looked like a pair of green scaly scissors, vanishing out the crack.

They all saw it go; the midwife, the doctors, and even the Princess’s wan face turned to follow it. The Princess even started to reach out a weak hand for the window, but the maid’s involuntary gasp, cut off, brought everyone’s attention to her. Then the Princess did scream, drawing her knees up.

The room dissolved into a whirlwind of activity. Both doctors went to their patient, one to take the midwife’s place on the stool and the other towards the foot of the bed. Several of the Princess’s ladies in waiting returned in a rush, fluttering and cooing.

The maid slipped out, but before she could make her escape she felt a hand grab her arm. She turned to find Frau Silber, the midwife.

“W-what…?” the maid trailed away as she realized she had no idea how to even phrase her first question.

“You must be trustworthy, if it felt safe to show itself while you were in the room,” said the midwife. “So you probably know it would be best for everyone if you speak of this to no one.”

“Of course not.” The maid shook her head. “I’m not certain anyone would believe me.”

“Likely not.” Frau Silber’s lips twisted in a half-smile. “Still, if I ever hear a rumor, I’ll know where to start. Trust me when I say that I can find you.”

The maid believed her. Whatever had just happened in that room had gone past miraculous into otherworldly. But the doctors had summoned the midwife, so they obviously knew about her and what she did. This was not precisely reassuring, but it was something to grasp at.

“But what…” the maid tried again. “What…how…?”

“Her Highness made a bargain, and that was the result of not following instructions,” said the midwife.

The maid’s eyes grew huge. “Are you saying that Her Highness made a deal with—with—” She just couldn’t picture the pious Princess having anything to do with such evil.

“Nothing so dire,” the midwife said with a shake of her head. “Worry not. Her Highness’s immortal soul is perfectly safe, as is that of the child she is bearing even now. But there is magic in the world, and sometimes to get what you most want, you have to make a bargain and accept the consequences.”

With this cryptic statement, Frau Silber took her hand off the maid’s arm and disappeared in the direction of the passage the maid had brought her in by, carrying her basket of herbs with her. The maid blinked several times to clear her head, realized it had been some time since she’d eaten, and headed for the servants’ hall in a daze.

She hadn’t even finished her meal when a breathless footman brought the news: the Crown Princess was delivered of a healthy daughter. Shouts of joy and groans of disappointment sounded from the staff. The maid tried to act normally, smiling and toasting everyone with her cup of wine, but inside she was still in turmoil. Frau Silber had said the Princess hadn’t made a deal with anything diabolical, and this the maid had to believe. She clung to that like a sailor holding onto wreckage from a drowning ship. But nothing would ever be the same.

When she was called in to tend the Princess later that evening when most of the fuss had died down, at first she could hardly look her mistress in the face. The baby cooing in its rocker was easier, though the maid could not see its rosy cheeks without remembering the way the Princess’s belly had heaved, and the green forked tail disappearing out the window.

However, when she did finally meet the Princess’s eye, her heart melted and she could not harden it. Princess Stéphanie’s face was waxen, her eyes sunken and hollow. Her lower lip trembled, and she looked small and young lying there in the big bed.

“Your Highness, I…” began the maid.

“You saw it all,” whispered the Princess. The maid nodded. “I can’t begin to explai

n,” the Princess said miserably. “Except that I gambled, and I’ve lost.”

“The midwife said something like that,” recalled the maid, “but she didn’t say anything else.”

“I did what I thought was best, for the good of the Empire. I failed. Now all that is left is to make certain she,” here the Princess smiled at the burbling form in the cradle, “grows up well, and to know her own mind so that what happened to me will not happen to her. I understand if you want to leave, after all of this, but I…I hope that you will consider staying. It would be a great comfort to have someone close to me who knows…what happened.”

If she had said anything else, the maid, who had indeed been contemplating handing in her notice, would have left that very night and spent the rest of her life trying to forget that she’d ever worked for the royal family. But the way the Princess spoke of raising her baby daughter told her what she’d needed to know. There was no way a woman this concerned with braving the fallout of whatever bargain she had made and lost had made any kind of deal with the darkness. Someone like that needed support, not desertion.

“I’ll stay,” the maid said. “For your sake, Your Highness, and for hers. I won’t ask what happened unless someday you feel you can honor me with that confidence.”

The Princess’s face brightened, and lost some of its waxy cast. “I can ask for no more. Now, will you please bring her to me? I would like to get to know her better…the one I have left. And I will pray every day for the one I lost.”

They both glanced at the window, only once, and then gave their full attention to the beautiful, perfectly formed infant girl.

Chapter 1

October 1898. Wildeshausen, Germany

Wilhelmina Beck made her way through the market, basket on her arm. She waved cheerfully to neighbors. A few stopped her to ask how she fared, or to rest a hand on her belly and feel the child within kick.

“Not long now,” was an oft-repeated litany, by Wilhelmina and others. Smiles sparkled back and forth like sunrise on a flowing river. Everything seemed bright and fair this crisp autumn morning.

The Dragon & the Alpine Star

The Dragon & the Alpine Star